Nell Darby details the history of the statute fair, or mop fair, where servants tried to find work, but could became the victims of crime instead.

In my local town, a fair is held twice a year. It’s a rather standard event; there are fairground rides, stalls where you can shoot a can to win a soft toy, or a goldfish in a bag of water, and where you can buy candyfloss or toffee apples. It’s old school; but its name harks back to an older past – it is known to all as ‘the Mop’.

It has it origins in the statute fairs that have existed for centuries. Also known as a hiring fair or mop fair – hence my town fair’s abbreviation – these were traditionally held in order for agricultural servant to advertise their availability for work, and for employers to find suitable workers. Although traditionally held in the Midlands and south of England in late September or early October – Michaelmas in the agricultural calendar, when harvesting for the year had been done – others were held in November (in the north of England) or April. The mop fair was tied to the seasons and to the harvests, reflecting its status as a place in rural societies where agricultural workers were hired.

The hiring fair had officially started in the 14th century, when Edward I passed the Statute of Labourers in 1351. The 1563 Statute of Apprentices legislated for a particular day of the year when the local constables would proclaim the stipulated rates of pay and conditions of employment for the following year. As fairs were already popular events, seeing many local people attend, they became the main place where workers and employers would assemble to be matched with each other. In 1677, an act endorsed the annual bonds or terms agreed between masters and servants at hiring fairs, and the events took on the alternative name of statute fairs. However, it was noted this year that in north Oxfordshire, at least, it had “always been the custom at set times of year, for your people to meet to be hired as servants”, showing that the statutes being passed simply formalised a process that had existed for some time previously. In some areas, the mop fair was held a month after a previous statute fair, in order to give still unhired servants a second chance of finding employment, or to get work for servants who had been hired at the statute on a month’s trial, and then let go at the end of that month. These second fairs were often known as a ‘runaway mop’, because those who had already been hired at the earlier fairs were returning from those employers to seek new ones.

King mop and his attendants

By the 1820s, there were certain traditions and customs involved in the mop fair. In Hereford in 1825, for example, the proclamation of the new “Statute or Mop Fair” in the city involved the character of King Mop – a local man in green silk robes, large hat and feathers, sitting on horseback – parading the local streets while reading out the proclamation, attended by six boys carrying mops. This fair was held in May rather than the more traditional September, and involved King Mop stopping at the King’s Head inn and sending one of his mop boys in to fetch him a pint of ale “which he quaffed amidst the applause of assembled hundreds”. [The Morning Post, 24 May 1825] Almost as an aside, the local paper – the Hereford Independent – noted that “there was a good attendance of servants at the fair, and the hiring seemed to go on briskly”. [repeated in The Morning Post, 24 May 1825] Servants also had their own names – male servants seeking work at the fair were ‘Johnnies’, and female servants were ‘Mollies’. Even the use of the name “Mop” was seen as a regional tradition; Joseph Wright, at the end of the 19th century, described it as a dialect name for a “statute fair for hiring servants and farm-labourers” only in certain counties, which he names as Middlesex, Lincolnshire, Leicestershire, Northamptonshire, Warwickshire, Worcestershire, Shropshire, Herefordshire, Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire, Berkshire, Huntingdonshire, the Isle of Wight and Wiltshire. In other words, ‘the mop’ as a term was a Midlands and Southern phenomenon.

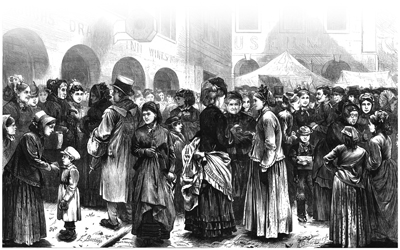

These fairs were an important arena for both male and female agricultural servants to bargain with employers, and arrange their work for the next year. Agricultural work in rural England generally ran from October to October, although there were some regional differences. These yearly hirings usually, although not always, included board and lodging for unmarried employers, and wages were generally paid at the end of the year’s service. However, this practice varied from place to place, with some workers paid weekly, fortnightly, and so on. Hirings had an inevitable link to the settlement laws, with some unscrupulous employers seeking to end a servant’s employment shortly before the end of their year. This was because, under the settlement laws, a servant would gain a settlement in his place of employ if he worked there consistently for a year. This meant that the employer’s parish would have to pay relief for the servant if he became poverty stricken through illness or subsequent unemployment. Therefore, some employers – who may have had to pay rates to cover their parish’s poor relief – may have tried to limit the number of people who could claim this relief by ending an employment early. And there were few formal contracts in terms of stating when earnings would be paid. Instead, at hiring fairs, workers would gather in the street or local market place, often carrying a badge or tool to show what kind of work they did. For example, shepherds held a crook or a tuft of wool; dairymaids carried a milking stool or pail, and housemaids held brooms or mops – hence the origin of the third name of ‘mop fair’. They would meet with local employers and the latter would choose who they wanted to employ. Once that decision had been made, they would give the servant a ‘hiring penny’ – more often a shilling, but referred to still as this term – to show that an agreement had been reached. Once the hiring penny had been given, the servant would remove the symbol of their availability and employment type, and wear bright ribbons to show that they were hired. They would then spend their penny at the stalls which were set up on the fair.

Quarter Sessions

Not all work matters were satisfactorily agreed at the mop. The Warwickshire Quarter Sessions of 1859 heard that a Mr Barbury of Newman Paddocks, Monk’s Kirby, had some time ago agreed to hire a 16-year-old boy at the Michaelmas Mop Fair in Leicester. However, he had failed to get any references for him from previous employers, the servant had committed arson, setting fire to Barbury’s home, and had subsequently been transported for ten years. Mr Barbury subsequently became a key force in a drive to monitor events at mop fairs, and to get police involvement in how they were run. He had sent a letter to the Quarter Sessions to warn them of “the many evils arising out of the present system of engaging agricultural labourers, ploughmen, dairymaids, or carters, at these fairs”. Statute fairs were regularly held at 27 places just within the Warwick district, and that “they are more or less productive of crime. Drunkenness, picking pockets, fighting, with phases of the ‘social evil’ [drinking] are placed in this category”.

These crimes came about because statute fairs were, as the name suggests, places for enjoyment as well as work. The Evesham Mop Fair in 1855 was, according to Berrow’s Worcester Journal, “well attended by masters, mistresses, and servants – male and female. The hiring was rather slack as to the men, but there was a great demand for female servants at good wages. There were plenty of amusements for the pleasure seekers”.

But as the Warwickshire Quarter Sessions heard, the mops not only attracted vendors of food and drink, but also thieves and drunks. They had become, by the early Victorian era, associated with crime, drunkenness and immorality. In April 1839, a case was heard at the Oxford Assizes involving a John Goodman, who was accused of violently assaulting John Love at the previous Chipping Sodbury Mop Fair on 28 September 1838. Goodman and Love had both got drunk at the fair, and later on in the evening, they had been involved in a street fight outside the town’s Bell pub. It ended with Goodman being accused of stabbing Love. Nothing was found on the defendant, so he was accused simply of assault rather than a more serious offence, and was imprisoned for six months. In 1861, Dorcas Davis, aged 17, was assaulted as she tried to leave the Gloucester Mop Fair at 11pm. She was attacked by some 12 boys and men, aged between 13 and 20, who “threw her down”. One of them got on top of her chest while she was on the ground, another put his hand over her mouth, and they then tried to rape her. Luckily for Dorcas, another man interrupted the gang, and they ran away. When she bravely gave evidence in court, Dorcas noted that she had been at the mop since 10am that morning, and that one of the men, who she knew by name, had been drinking for at least five hours before the attack.

By the 1850s, steps had been made in various areas to discontinue the statute fair, and to replace them with a more simple affair – the 18th century statutes were seen as a more polite event that should again be aspired to. In Stoneleigh, Warwickshire, a ‘register office’ was created, to ensure that statutes were run in the same manner from place to place, under the jurisdiction of magistrates and managed by the police. It was hoped by the Warwickshire gentry that this system would gradually expand and become the norm.

Over the 19th century, the nature of the fairs changed. As early as 1830, one woman, Mrs Sherwood, wrote, “I have heard my mother say, that formerly each person carried a mop, or a broom… or some other badge denoting the office in which they desired to engage; but this was done away with before my time.”

From employment to entertainment

By the end of the century, there was no doubting that the main function of the fair was now entertainment, not employment. By 1898, the Stratford-upon-Avon mop fair, which was described in the press as “ancient – in existence several hundred years”, was still attended by “thousands of persons”, but could no longer be described as a hiring fair for servants. Whereas once, legally binding annual contracts were decided there, and entertainment was little more than the roasting of oxen and pigs on public spits, and the Daily Mail noted that “of late years, it has become little more than a huge pleasure gathering”. Some hiring was still carried out, though, and hiring fairs continued until the World War II in some places, although their popularity decreased after the passing of the 1917 Corn Production Act, which established the Agricultural Wages Board. Today, certainly in the Cotswolds, the mop fair continues to be held every year – and the merriment, the spending of money on enjoying oneself, and the name are the same as centuries ago. Only the main aim of the fair – the employment of agricultural servants – has disappeared.

Finding out about the Mop

The best sources of information about Mop Fairs are newspapers and court records – the latter showing how the statute fairs became associated with crime and disorder, particularly as the 19th century progressed. Both Quarter Session and Assize records, available through www.ancestry.co.uk and www.findmypast.co.uk, cover mop-related cases, from drunken behaviour and theft to assault and rape. Newspaper reports, through www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk and Gale’s 19th century newspapers database, cover these cases too, but also detail the nuts and bolts of individual statute fairs – how much business was conducted there, how well attended the fairs were, and valuable social detail in terms of the weather, the employers and workers who visited, and the ‘Sunday best’ worn by many of the servants seeking employment. It is worth finding crime reports in the newspapers first, and then cross-referencing with cases listed in court records, as criminal registers may not always detail the location of the offence, and it takes a newspaper report to note if an offence took place at the mop fair. What newspaper reports also show is the gradual decline of the mop fair as a location for hiring servants; by the 1890s, it is clear that it was more of a street fair for entertaining locals, and that its hiring function was now only a small part of its attraction for people.