In 19th century Scotland, one criminal case shocked the country, and also highlighted issues of gender and class, writes Nell Darby.

She was a young woman from the wealthy, educated class of Glasgow society – one who had a bright future ahead of her, in demand as a potential wife, and the life and soul of life in the Glaswegian assembly rooms and at dinner parties. Yet Madeline Smith was soon to shock Scottish society, by breaking not one, but two taboos. She had a sexual relationship with an immigrant from a different background to herself, despite being young and unmarried; and she was to be accused of his murder, when she changed her mind about being with him and was blackmailed by this unpleasant man.

Madeline Hamilton Smith was born in March 1835, the first child born to architect James Smith and his wife Elizabeth: the couple would go on to have four more children, and lived in an affluent part of Glasgow. In 1855, barely aged 20, Madeleine was introduced to a young man from Jersey, Pierre Emile L’Angelier – known by his middle name – by her neighbour, the middle-aged Mary Perry. There was an instant attraction, and the two started to meet in secret – as Madeleine knew her father would disapprove of L’Angelier. They wrote numerous, passionate, love letters to each other, and after they started sleeping together, Madeleine took to referring to herself as Emile’s wife, giving herself the name of ‘Mimi L’Angelier’. However, over time, Madeleine became conflicted about the relationship, as she also became aware of her lover’s temper and weaknesses (he was later described in one newspaper as a ‘meaner and more contemptible scoundrel it would be difficult to concieve’). She also knew how much her family would be shocked by her relationship – not just who it was with, but how sexually intimate she had become with this man.

Her father wanted her to marry a suitable man – the wealthy William Minnoch. Unable, or unwilling, to disobey him in this matter, she now found herself engaged to one man, whilst sleeping with another. She knew that Minnoch would stop the engagement if he found out about L’Angelier, and feared this. However, her life was now complicated by seeing L’Angelier in secret, whilst also arranging to visit, and be visited by, her new fiancé, without L’Angelier finding out. He was suspicious of Minnoch, despite Madeleine assuring him that Minnoch was simply a friend of the family’s.

Madeleine knew that her situation was fragile, particularly as she had written many incriminating letters to L’Angelier, in which the sexual nature of their relationship was made explicit. If these fell into her father’s hands, they would have a huge impact not just on her life, but the lives of her family – they could face being ostracised by their friends and neighbours in this Victorian society. She therefore asked Emile to return the letters, but he refused, instead choosing to try and blackmail her, threatening to give the letters to her father instead or her.

She felt she had to continue seeing the lover she by now resented; but after each visit, Emile told friends he felt unwell. He recorded in his diary and in letters his illnesses, and in one letter, suggested that Madeleine might have poisoned his coffee. Finally, on 23 March 1857, he became ill again, and was prescribed morphine by his doctor. The following morning, he was discovered dead in his lodgings, killed by a large quantity of arsenic found in his stomach during his post-mortem.

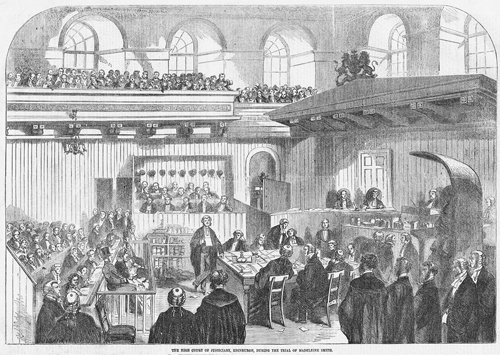

Madeleine had, shortly before, fled her home for the family’s holiday cottage; in her absence, though, the letters from her to Emile were discovered, and the police set out to arrest her. She was duly tried for murder in Edinburgh, but the verdict was ‘not proven’. This meant she had not been found guilty; but neither had she been found innocent – simply that the charge could not be proved. Her life could not, therefore, resume where it had left off. William Minnoch no longer wanted anything to do with her, and her parents ended up rejected by their old friends and had to start a new, isolated, life elsewhere.

Madeleine lived to the age of 93, marrying twice, and living in both London and the United States. Her death was reported in the Dundee Courier with an air of surprise: ‘Only the very old will be able to recall the case itself, and they will do it with a shock of surprise produced by today’s news that till a week ago, the notorious Madeleine was still alive.’

She had attempted a life of relative anonymity after her trial, but today remains infamous for her association with Emile L’Angelier’s death. Did she kill the bad-tempered, irrational man who had sex with her and then attempted to blackmail her? Did she regret the relationship when a more socially-acceptable marriage presented itself to her, making her feel as though she had no choice but to kill her lover? Or was Emile’s death simply the result of a self-administered dose of arsenic for medicinal reasons? The matter is still being debated; in favour of Madeleine’s innocence is the fact that Emile was known to be a regular user of arsenic, that he sought revenge on Madeleine for going cold on him, and the suspicion that his diary was written later, with Emile trying to portray Madeleine in a bad light as part of his blackmail attempts.

Whatever the truth, Madeleine’s case has all the makings of a Victorian novel, with her desire for an unconventional, sexually satisfying life resulting in the inevitable comeuppance and tragedy. Yet it was real life, and a life that showed the pressure on girls to conform and behave – or face the consequences.