Colin Waters recalls a Scottish industry that once employed thousands of workers.

Few people in Britain are aware of Scotland’s once massive oil shale Industry. For over a century, it was a major producer of oil and derivatives employing hundreds of Scottish and ‘incomer’ workers. At its peak in 1913, the industry employed an estimated 10,000 workers – although the number of men employed at any one time peaked and troughed on a regular basis. Yields varied between 20 and 40 gallons of crude oil per ton of shale, but as demand for paraffin and its derivatives began to fall, the late 1950s saw a steep decline in production. By the 1960s, it had ceased altogether.

It was in 1847 that a Scottish chemist who attracted the name James ‘Paraffin’ Young developed a method of making paraffin oil, lubricants and wax from cannel coal – a soft rock that has the qualities of both coal and shale. After Young’s patents ran out in 1865, other Scottish shale oil works went into business, and Young established his own Young’s Paraffin Light and Mineral Oil Company at Addiewell, West Lothian.

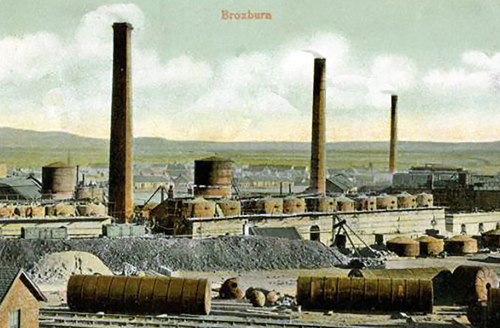

Most of the major mines were situated in a compact 50 square mile area that encompassed South Queensferry, Blackness, Fells Camp, Dunnet, Broxburn, Pumpherston, West Calder, Tarbrax and Philpstoun as well as other places in between. Shale oil production also took place in areas of Fife and Midlothian. Although well over 100 mines were in production in the early 1900s, less than half were active at any one time. This was because mine production rarely lasted more than five years. Consequentially, when searching for these men, it’s worth remembering that workers and their records changed locations on a regular basis.

The workforce

Peak employment years were the late 1800s to the early 1920s, with men being employed to carry out a large number of tasks in a variety of conditions. Some mines, for example, worked open cast mines (in other words, those dug from the surface), whilst others mined over 1000 feet deep. Most of those who were actually described as miners or faceworkers were employed at the rock face, although you’ll come across other names. The term ‘contractor’, for example, was generally applied to men who dug the mine access shafts, whereas a ‘placeman’ was a workface manager who was assisted by a ‘shift-face man’ and ‘drawers’. They filled the rock containers called ‘hutches’, and would draw or pull them to the shaft incline.

Groups of men usually worked together in shifts, producing about nine tons of raw materials on each shift, an amount that increased to 12 tons per faceworker when conveyor belts were introduced in the late 1940s. Those on the afternoon shift were responsible for moving equipment, roof supports and conveyors ready for others who arrived for the night shift to bore holes and fill them with explosives before firing them to bring down the shale to the mine floor. Finally, the day shift arrived to remove the shale and set up the mine ready for the next afternoon shift workers.

The processes involved in turning shale rock into oils, wax and bi-products would fill a book, but you’ll find an excellent and succinct description online of all the processes involved, including mining, crushing and even candle making, in a reprinted article from a 1902 issue of the West Lothian Courier entitled ‘A visit to the Addiewell Oil Works’ (see tinyurl.com/ybacggex).

Dangers

Unlike in coal and other mines, naked flames were allowed. This appears to be because the deadly ethane gas known as ‘firedamp’ was largely absent from shale mines. Even so, mine owners were advised to ensure adequate ventilation for the workers ‘just in case’. This was a wise precaution because when procedures weren’t followed adequately, firedamp explosions did occur. Nine men were burned during explosions in the 1930s, and further blasts occurred in the 1940s and 1950s. Another hazard, a choking gas known popularly as ‘choke damp’ (carbon dioxide mixed with nitrogen) caused its own problems. In addition, falls, and being run over by shale-tubs, accounted for many more accidents and fatalities. Though all catastrophes were tragic, in comparison with other mining activities they were relatively few. For example, during the five years following 1933, Winstanley mine was being worked by around 1500 men, but reported only 11 serious injuries and seven deaths – a tally that was very favourable compared to similar statistics from coal and other mines at that time.

One-stop research

Anyone researching the industry has a valuable resource in the Museum of the Scottish Shale Oil Industry Scottish Shale website (www.scottishshale.co.uk/). This virtual one-stop information website is packed with lots of information regarding every aspect of the industry including company records, photographs, transcripts of interviews conducted between 1983 and 1990, a database of employment records, a section on ‘notable worthies’, and much more. You may well find this is the only resource you’ll need to carry out your research, and it’s rare to find a website that serves its purpose in such a well thought out and comprehensive manner. Using its easy to negotiate interface, users are able to wander through virtually every facet of the history of Scottish shale mining using its various sections. These contain not only the histories of each individual company, a database containing the names and work details of employees (remember though, not everyone worked underground), reproductions of actual employee record cards, and free downloads concerning a whole range of specialist aspects of the trade including the lives of the mining ponies, lists of accidents and casualties, and the ‘Bungrange Index’ – which itself is sub-dived into various other subject headings.

Oil works were attached to the various mines, where topside workers heated up the shale in large ovens in order to extract the oil. Eight tons of shale produced only ten barrels of oil and left behind six tons of waste that ended up being dumped on large spoil heaps known as ‘Bings’. The remains of these still dot the landscape in shale mining areas such as the north of Broxburn, where oil was processed opposite the Bing. Broxburn was actually one of the largest oil works, producing not only paraffin and sulphuric acid, but also soap, candles and other by-products.

The end of hard manual labour began with the introduction of steam engines which were used for haulage, powering the winding gear, operating ventilation fans and pumping water. The first electric power was introduced in 1879 by the Oakland Oil Company at Duddington, although its use was by no means universal. It wasn’t until the 1930s that power stations were established to service the areas mines. By the 1950s, the workforce had greatly reduced and by the 1960s, the Scottish industry closed down forever.

James ‘Paraffin’ Young (1811-83), father of the industry

James Young was born in Drygate, Glasgow, in 1811. He began life as an apprentice to his carpenter father John, but later became a chemistry lecturer’s assistant at Anderson’s College (now Strathclyde University). In 1838, Young married his wife Mary, and the following year they moved to Newton-le-Willows, which

was then in Lancashire, where he took a managerial job at Muspratt’s chemical works.

By 1844, he was working for Tennant, Clow and Company of Manchester. Three years later he succeeded in making mineral oils from natural petroleum seepage at Riddings Coal Mine in Derbyshire, naming one of the oils and its wax

as ‘paraffine’ and patenting his methods.His continued success led him to step back from business and to enjoy his extensive earnings, buying land¸ travelling, yachting and following his other scientific pursuits. At the age of 71, Young, by then a widower, died at Wemyss in Fife. He was later buried at Inverkip churchyard in Renfrewshire.