The Gittins family were well established in Mostyn, north Wales, where they mined coal. But what would they do when their mine closed? By Rick Kitson.

Mining in Mostyn has taken place since 1261, and it has always been a dangerous occupation. As well as the risk of the underground workings collapsing, throughout the last few centuries, gases have leaked from the seams of coal, causing explosions. There was a major explosion in 1676, one in 1806 when 36 were killed, and another 11 died in 1840.

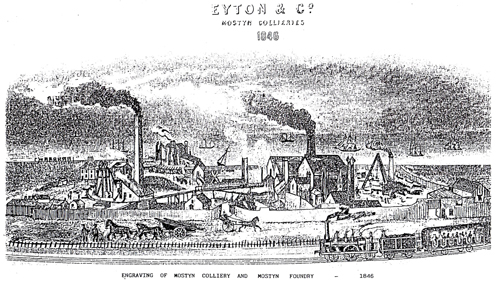

But by the time of this last explosion, coal had become the essential fuel that powered the Industrial Revolution, the steam engines that pumped water and drove industrial machinery. Coke (cooked coal), along with iron ore, was used to make iron and steel. The Mostyn Coal and Iron Company, with its Quay colliery, and the adjacent ironworks were the main source of employment in the town, with iron ore imported over the quay, and the pit fuelling the foundry. The mine produced between 200 and 250 tons a day, with 100 tons going to the ironworks. The Quay mine had been sunk in the 1860s; its main shaft was 210 metres deep, and the mine extended over 800 metres out under the wide estuary where the River Dee meets the Irish Sea.

This was where my maternal grandmother’s grandfather, John Hollingsworth Gittins, worked. How do I know this? The usual birth, marriage, death and census records had taken me back in time, and showed me that he was a miner, and that the Gittins family lived in Red Street, Rhewl, Mostyn. But which mine did John work at? I joined the Clwyd Family History Society (www.clwydfhs.org.uk) and corresponded with a fellow member, Colin Parry. He remembered a 2003 article in in the Clwyd FHS magazine, which contained a reprinted contemporary essay from 1889 on the flooding of the Quay Mine at Mostyn. This listed many of the people who worked there, and where they went after the flood – including John Gittins and his family. The Gittins family were long-established in Flintshire. John’s ancestors are in the parish and census records, traceable back to Peter Gittins, who was baptised in 1686. John’s father was a miner, and his grandfather a coke agent.

Catastrophe

The Mostyn Quay mine was worked on the ‘pillar and stall’ method. As the coal was extracted, some was left in pillars to support the roof. Clearly, a balance had to be struck between profit and safety, to decide how much coal needed to be left in the supporting pillars. The pillars also would need to be kept in sound condition, and not damaged during the ongoing mining activities. There would be much discussion of the state of the pillars, because on the evening of 22 July 1884, the miners’ other enemy, water, entered the mine rapidly, and in huge quantities. Attempts to pump it out made no difference at all, as it was coming in from the sea. Although the ironworks would continue by importing coal from Lancashire, the mine and the jobs of the miners were lost. The effect on the community was catastrophic; as well as the direct loss of 200 jobs, families who had taken in lodgers who worked in the pit lost their livelihoods, and shops and carters lost their businesses.

As it became clear that the mine would never reopen, the miners sought work elsewhere, some at the ‘Black Parlour’ pit at Point of Ayr, many in Prescot, near Liverpool, and some emigrated to far-flung places. A Mostyn man, Evan Parry, had left before the flooding to become manager at Wharncliffe Woodmoor colliery in Barnsley, and many followed him there to Yorkshire.

The Barnsley move

After some time travelling to Barnsley on a weekly basis, John moved his family there. John’s wife Ellenor died on 11 August 1890, and was buried back in Mostyn in the cemetery at the Bethel Welsh Calvinistic Methodist Chapel – the gravestone is there today. This meant that by the next census in 1891, John was heading the household as a widower. One of his daughters was still at home, as was his son William Thomas with his new wife Martha, whom he had married a month after his mother’s death. The family were in the village of Smithies, just to the southwest of Carlton, and there were many other Welsh refugees – so much so that the Smithies and Carlton area was known as ‘Little Wales’. A Welsh church was established in 1890, and had its own building in Carlton by 1902.

Melvyn Jones, in a 2003 article, lists the pioneering families from the Mostyn area, and John Gittins is among them. But ten years on, in the 1901 census, John was no longer in Barnsley, and had gone to live in Eldon, Durham. However, when he died two years later, in February 1903, he was buried in the same place as Ellenor, in Mostyn.

In June 1903, just after her grandfather’s death, my grandmother Louisa Eva was born in Hawson Street, Wombwell, where William Thomas Gittins (who was still a miner), Martha and their family were living. They were no longer in ‘Little Wales’. By 1911, they were living in Windmill Terrace, on a hill overlooking Barnsley town, and that was Louisa Eva’s home address until she married Herbert Fisher from Batley in 1924. His father was a butcher, his mother a weaver, and she had met him whilst working in the household of a Mrs North in Batley.

The couple moved to Otley, a market town in Wharfedale, Yorkshire, and set up their own butcher’s shop, well away from the smoke and grime of the collieries, and achieved the coveted transition to self-employed status. Herbert and Louisa ran the shop for 38 years until their retirement in 1965. They then moved to The Crossways in Otley, and spent many happy years with their growing family of grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Louisa died in 1984, and Herbert in 1991. n

Further reading

- Robert Lindsay Galloway, A History of Coal Mining in Great Britain, David & Charles, 1969. ISBN 0715343432.

- Lewis Jones, The Coal Mines of Mostyn and the Men Who Worked and Died in Them, Lewis Jones, 1997. ISBN 0953036804.

- Melvyn Jones, ‘Welcome to Little Wales’, in Memories of Barnsley, issue 25 (Spring 2013), available from www.memoriesofbarnsley.co.uk/backissue/25/

Digging for mining books

There are loads of online resources on mining – just follow your search engine! However, I did not find what I wanted on Mostyn this way. I was told of a book, ‘The Coal Mines of Mostyn and the Men who Worked and Died in Them’ by Lewis Jones. It was listed on Amazon and The Book Depository, but wasn’t in stock, and neither was it in the bookshops

I phoned in Wales or Liverpool either. Local libraries and inter-library loans didn’t work either – but COPAC did. COPAC (copac.jisc.ac.uk) searches UK university and research libraries, and the book was listed in five of these. Cambridge University Library (www.lib.cam.ac.uk) was the closest to me, and so a temporary reader’s ticket and a day out were planned, as the book could not be borrowed.I was initially overawed by the size of the library building, but was made welcome. The book was brought to me in the West Room of the library, where I read the details of the flooding of the mine, and what followed. It was a memorable experience, and I am glad I did not give up the search.