This Midlands city is about as far from the sea as it could be, but is very much at the heart of Britain’s industrial history, writes Andrew Chapman.

Derby today is a vibrant retail centre, but it is most notable for being an industrial powerhouse throughout two millennia of history. That history goes back to Roman times – Strutt’s Park includes the site of a fort built in AD50, and 20 years later a small town, Derventio, developed around what is now called Little Chester, on the opposite side of the river. Even in the Roman era, the area was known for its ceramic work – remains of 18 pottery kilns and metalworkers’ workshops have been found on the site of Derby Racecourse. Archaeologists have even found the names of two of the potters, Septuminus and Aesticus, who stamped their mixing bowls.

In Saxon times, Derby became the burial place of the martyred St Alkmund. Sadly the Victorian church that bore his name – which turned out to be on the site of previous places of worship dating back to the ninth century – was demolished in 1968 to make way for the ring road. The city’s much-loved artist Joseph Wright was originally buried here, but now his remains are in Nottingham Road Cemetery and his headstone at the cathedral. Meanwhile a Saxon cross dedicated to St Alkmund, and the saint’s impressive sarcophagus, can be found in the city’s museum (see ‘top three’ box).

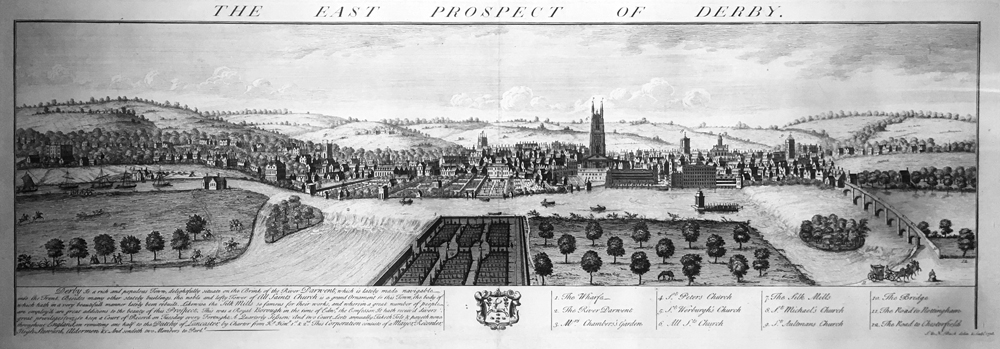

The cathedral has only had this status since 1927 (and Derby has only been a city since 1977) – before that it was the parish church of All Saints, but this too has a heritage going back to Saxon times. There are no remains of the original church left, and the oldest part now is the 16th century tower. The cathedral is notable for the tomb of Bess of Hardwick, the Elizabethan businesswoman who rebuilt Chatsworth House.

By Norman times, the town was thriving – in 1066 it had 243 burgesses and 14 mills, although 20 years later, the Domesday survey listed only 140 burgesses and 10 mills, a decline attributed to William I suppressing a rebellion in the Midlands. For a while Derby lost status to Nottingham; in 1204 it gained its own royal charter offering similar liberties to Nottingham, but remained under the other city’s sheriff (Hood-hating or otherwise) until the 16th century.

In medieval times Derby had a market, a mint, a guildhall and a moot hall, as well as 12 churches or other religious houses, and numerous mills on the River Derwent and Markeaton Brook between which the centre was sandwiched. Various street names imply there was a castle at one time, although it has remained elusive to archaeologists.

Even before the Industrial Revolution, Derby thrived as a centre of trade. It was particularly known for lead and iron work, as well as alabaster, leather work and cloth, horn working and tanning, plus of course the inevitable pottery – in the 13th and 14th centuries this was made just to the north of the town.

Even though the Silk Mill is currently closed for a major revamp (as of spring 2019), the site is well worth wandering around. Perched next to the River Derwent, it is on the site of the mill built by George Sorocold (c1668-c1738), now regarded as Britain’s first civil engineer, between 1717 and 1721. This mill is regarded as the world’s first factory because it brought the entire production process, driven by a common source of power, under one roof for the first time. Fire damage means that the building there today, other than the tower and undercroft, mostly dates from 1910.

Another brush with history came in the form of a visit from Charles Edward Stuart, aka Bonnie Prince Charlie, in December 1745. For a couple of days he made Exeter House his headquarters – this mansion no longer exists, but some of its panelling, and a mock-up of the prince at his desk, can be seen in the city museum. Charlie came with an army of thousands of Highlanders in search of support, and Derby offered more than anywhere else in England, with the townsfolk raising £3000 for his cause. However, larger armies were heading this way to tackle him, and he retreated to Scotland, to be victorious at Falkirk and ultimately humiliated at Culloden.

Derby’s fame for porcelain began in the late 1740s, with the arrival of André Planché, of Huguenot origins. He briefly teamed up with the enameller William Duesbury, and the latter then single-handedly made the business a roaring success. Today the Royal Crown Derby Visitor Centre celebrates their achievements (see www.royalcrownderby.co.uk).

What is now Osnabrück Square was once part of the garden of the Duke of Devonshire’s house in Cornmarket. The land was later purchased by cotton pioneer Jedidiah Strutt, who built a six-storey calico mill here in 1793. Strutt was the inventor of a machine for making hose known as the Derby Rib Attachment. Although intended to be fireproof, unfortunately the mill caught fire twice and after the second occasion, in 1876, it was demolished. From the 1920s to the 1980s it was the site of the city’s fish market.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Derby became a hub of engineering, science and modern thought. Erasmus Darwin founded the Derby Philosophical Society in 1783; Joseph Wright was a luminary of the Royal Academy; and James Fox made machine tools to support the area’s industries.

In the 1840s, Derby became the headquarters of the Midland Railway and a pivotal railway manufacturing centre. The world’s oldest surviving locomotive turning shed, Derby Roundhouse (1839), survives today as an events venue.

The city’s industrial focus was boosted again in the early 20th century with the arrival of the Rolls-Royce car and aircraft factory. The railway connection continued, too: the first mainline passenger diesel-electric locomotive was unveiled at the Derby Works in 1947. Rolls-Royce remains based in Derby today, and Toyota has a major factory near the city, so those two millennia of industrial heritage look set to continue.