Liverpool’s fortunes have been shaped by its port and associated industries – and, as Nicola Lisle explores, your ancestors could have been involved.

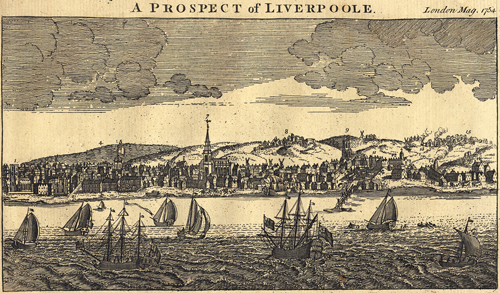

Originally known as Liuerpul, meaning ‘muddy creek’ or ‘pool’, Liverpool was once little more than a small agricultural settlement within the historic county of Lancashire, clustered on the banks of the River Mersey. Despite being granted a Royal charter by King John in 1207, it remained a small market town for centuries, relying on fishing and farming for survival, and suffering economic decline during the Middle Ages. By 1571, the situation was so desperate that the locals appealed to Elizabeth I to help the “poor decayed town of Liverpool”. It wasn’t until the 17th century that the town began to prosper. The silting up of the River Dee meant that the nearby city of Chester gradually diminished in importance, paving the way for Liverpool to develop its potential as a port. Soon, Liverpool had established trading links first with Ireland and later with America and the West Indies, laying the foundations for its status as one of the UK’s major ports.

Maritime town

Liverpool’s rapid growth began after the Restoration in 1660. By the beginning of the 18th century, Liverpool was enjoying a burgeoning overseas trade in sugar, tobacco, grain and timber. This in turn spawned the development of an equally successful shipbuilding industry. Before long the town’s natural harbour was struggling to cope, and it was clear that a larger, purpose-built dock was needed. Following an Act of Parliament in 1709, the first of Liverpool’s famous docks was built by London engineer Thomas Steers. Later known as Old Dock, it opened in 1715 and was the world’s first commercial enclosed wet dock. Within 20 years, Old Dock had become too small as Liverpool’s growth spurt continued, and in 1736 Steers oversaw the construction of Salthouse Dock, along with a Customs House, dry dock and pier. Throughtout the 18th century an intricate network of enclosed docks developed along the waterfront, including George’s Dock (1771), Manchester Dock (1780), King’s Dock (1788) and Queen’s Dock (1796). At the same time, vase numbers of spacious warehouses were built alongside the docks, making Liverpool one of the largest and most efficient ports in the world.

’Black Gold’

The most shameful episode in Liverpool’s history is its involvement in the transatlantic slave trade, which became its main preoccupation during the 18th century and transformed it into one of the UK’s principal cities, second only to London in size and importance. The trade generated unprecedented wealth for the city, and many of its grandest and most elegant buildings arose from the proceeds of ‘black gold’. Liverpool’s first recorded slave voyage came as early as 1699, when the Liverpool Merchant exchanged British-made goods for around 200 African slaves, who were then shipped to Barbados. For the next hundred years, Liverpool ships transported African slaves across the Atlantic in filthy and overcrowded conditions, returning home with cotton, sugar and tobacco grown on slave plantations.

By the time slavery was abolished in Britain in 1807, Liverpool had become one of the world’s leading slave trade ports, accounting for around 80 per cent of Britain’s slave trading. At its peak, it is estimated that Liverpool had over 130 ships involved in the trade, and was carrying around 45,000 slaves a year from Africa to North America and the Caribbean. Even after the abolition of slavery, the practice continued well into the 1830s. By then, Britain was in the grip of the largest-scale mass emigration in history, as people sought new opportunities in America, Canada and Australia. Liverpool quickly became one of the UK’s leading passenger ports, and it is estimated that around nine million people set sail from Liverpool on emigrant ships during the 19th century.

Industrial Revolution

Liverpool’s other source of prosperity during the 19th century was cotton. The port was ideally placed to import raw cotton from America, India and Egypt, distribute it to Lancashire’s cotton mills and then export the finished products. The opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in 1810 enabled the raw materials and goods to be moved with greater speed and efficiency, adding considerably to Liverpool’s already booming economy. By the end of the century, Liverpool had become the largest cotton trader in the world, handling more than half a million tons annually. More docks were built to cope with the increased trade, most notably the famous Albert Dock, Liverpool’s first fully enclosed dock. Designed by Jesse Hartley, Liverpool’s Dock Engineer, it featured rows of well-ventilated, fire-proof warehouses and was modelled on St Katherine’s Dock in London. More than just a commercial success, Albert Dock was also architecturally splendid with its Doric columns lining the quayside. Its first warehouses were officially opened by Prince Albert in 1846, and the dock became the hub of Liverpool’s import and export activities, handling not only cotton but also rum, sugar, tea, rice, silk, ivory and spices from America, the West Indies and the Far East.

By the end of the 19th century, Liverpool’s global trading was beginning to decline, although trading with Europe continued beyond the turn of the century. Albert Dock’s usefulness ended with the advent of steam ships, which were too wide for the dock entrance. Nevertheless, as the 20th century dawned, Liverpool was still one of the world’s leading trading ports, with docklands, warehouses and factories covering an area of seven miles. It wasn’t until the outbreak of World War 1, which had a devastating effect on Liverpool’s population and economy, that its dominance as a port came to an end.